Puro SA: Tattooed Boy

By Ayesha M. Malik

Todo Chingón by Tattoed Boy

Just take one look around vibrant San Antonio and you’ll very easily see the art of the city all around you. Ray “Tattooed Boy” Scarborough, Jr. (Instagram: @tattooedboy123) is an artist and printmaker in San Antonio who has made a name for himself in the 210. Having launched his website with art for sale earlier this year, he also releases new prints in-person in limited “drops.” As an avid Tattooed Boy art collector, I have stood in those lines in hopes of scoring whatever he puts out next and added many of his pieces to my online shopping cart.

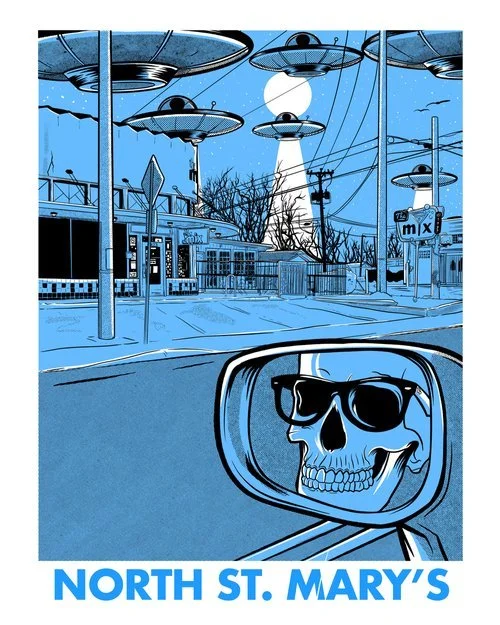

Of his large body of work, he illustrates the Puro SA spirit and landmarks in his very inconspicuously titled City Prints series. He lovingly calls them “tourist posters for locals.” These ultra-exclusive prints (of which there are only 50 hand-numbered and signed by the artist himself) spotlight San Antonio scenes with a surreal twist and invoke playful nostalgia. All the locales you know, love, and frequented at some time or another (if you’re not a pinche tourist) are screen printed by hand in single bold colors broken up by solid black, halftone, and white space–giving these prints a certain “comic book”-like quality. The graphics are striking and the quality is primo. The pride Tattooed Boy embeds in his art is palpable.

The City Prints feature spooky motifs and phantasmagorical flying animals, people, cars, and space objects surrounding infamous haunts like Hogwild Records on North Main, The Mix on North St. Mary’s, Faust on the Other Side of the St. Mary’s Strip, the Pioneer Flour tower in Southtown, the long-gone gondolas of the Brackenridge sky ride, El Paraiso Ice Cream on Fredericksburg, Skateland West, the old Lone Star Brewery on Lone Star Blvd, the stretch of I-10 where R.E.M. famously shot the video for Everybody Hurts in 1993, and the San Pedro and Hildebrand ghost bus with the busted Butterkrust billboard. Look deeply and discover a plethora of little easter eggs, like “Sup!” and “Lala” (a nickname for his mother, Oralia) scrawled in tiny corners.

Recently, Tattooed Boy’s prints were showcased among dozens of other local artists at San Antonio’s very own Paper Trail event this past summer, where he debuted a Wemby print to celebrate Spurs’ rookie Victor Wembanyama, as well as four new City Prints for Lulu’s on Main, End of Babcock, Waterburgers ? (featuring the Taqueria Jalisco housed in the iconic Whataburger A-frame building), and South Broadway Pig Stand. There were only a handful of these prints left over after the massive lines at Paper Trail SA 2023; however, they were all snatched up at a second-chance pop-up by Tattooed Boy at Second Saturday in December. Tattooed Boy’s prints are a hot commodity – and it’s easy to see why. (If you weren’t able to catch Paper Trail SA this year, it is a must for summer 2024. A one-of-a-kind, one-day art fair and exhibition, I spent more dollars than I had sense, but hey, support your local artists.)

If you were looking to get in on this wild fever-dream aesthetic and unique take on San Antonio for all the prints of places I just mentioned, it’s too late. Not a single one of these released City Prints isn’t completely SOLD OUT – I do apologize for breaking the news that you slept on local art. However, the series is not over. With new releases previewed on his Instagram and the “Coming Soon” portion of his website constantly, there’s no shortage of inspiration in the city for Tattooed Boy. Next up is the Tower Life building City Print in a brilliant blue surreal underwater scene with a mermaid, jellyfish, and giant octopus scaling up the side like King Kong. More than that, he’s got perennial prints for you to purchase and cherish at any time on his website, like the Weird Ass Pyramid building along 410, Woodlawn Lake Yacht Club, and Randy’s bingo hall.

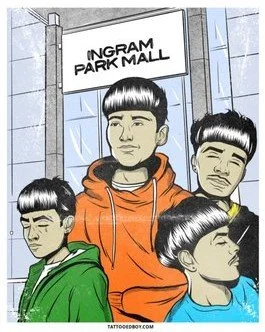

I snagged up some (read: a lot) of this museum-quality art and have been obsessed. His comic and pop-art influences are clear to see, wrapped up along with his Chicano San Anto upbringing and punk rock and alt-rock music like the Smiths (from whom the ‘Tattooed Boy’ moniker itself is derived). One of my personal favorite pieces is Ingram Park Mall with the four Edgars, cuh. If you’re confused by who Edgar is: don’t be. You’ve seen Edgar around town. It’s that high school kid running around the mall in skinny jeans with the mushroom/bowl “Marbach” haircut with the clean line-up and fade. They are undeniably San Anto, part of the rich cultural tapestry and youthful vibrancy of this city—which is exactly what Tattooed Boy captures in his art.

In addition to being a talented local artist, he is a devoted son and caretaker to his father, Ray Scarborough, Sr. On top of that, he has also supported the San Antonio Food Bank with his art. Tattooed Boy, like many San Antonio artists, is incredibly humble about what he does—despite leaving such an indelible mark on the art scene in this city. In fact, for the Spurs’ opening night this year, everyone in attendance received a free t-shirt emblazoned with The Coyote peddling basketballs on a paleta cart specially designed by Tattooed Boy in collaboration with San Antonio’s beloved NBA team. He’s even got two pieces featured in the Whataburger Museum of Art. It was a no-brainer to interview him for this Puro SA series.

Tell me about yourself. Who are you? Where did you go to school? What was your “scene” growing up? How did you get into art?

“I was born and raised in San Antonio and lived nowhere else, I went to Holmes High School, graduated ’94. Majored in Mass Communications at San Antonio College. I got a job in photography around the college era, just cap-and-gown graduation photos at Sam’s Studio [of SA]. Being in the punk scene and making art for flyers, I was just making artwork for myself and friends [and their bands]. If they had a show, I would do Sharpie art and was able to post it at Hogwild [Records].”

How did you pivot into making a name for yourself in the art scene in San Antonio?

“So, doing promotions [for friends], I started learning graphic design, which led to cleaner designs and it was easier to come up with stuff for bands. To have my artwork at Hogwild [Records] was like my own little gallery that I was invited to, even though anybody could put their flyers there. To me, it was a big deal, especially to see my friends be well promoted. My flyers were seen by a lot of people. A lot of them became famous, like Girl In A Coma. So, other people started hiring me, asking me if I could help them promote an event. I was drawing for myself here and there, but it branched off to where I was doing a lot of custom jobs for people—not necessarily my own artwork. It was a strange time before social media. Not a lot of people were showing their artwork as much as they are now, so I was scared to show my art, too. It took coaxing from my friends to do an art show.”

Where did you have your first art show?

“Around 2005, there was a bar called The Lounge that used to be a legendary punk club [in San Antonio]. My friends owned it and they said I could have a spot in the corner, so I showed six pieces of art I made. I was right next to the pool table, so I was in the way of people’s shots. I thought it was fancy. I’ve been grateful for those moments and for people giving me any type of opportunity. I think I sold one for $25 and I was like, ‘Wow! This is pretty cool!’”

How did you move from hand-drawn flyers to high-quality screen printed posters?

“All my favorite [punk rock] bands had these famous artists who would do these screen printed posters. That’s what got me into collecting actual posters of bands I liked, which got me into wanting to [make posters] myself. I thought it’d be cool if I learned how to screen print. Later on, during COVID, that’s when I sat myself down and learned how to screen print. I was dead set on learning it. Jessie from Cat Palace [Screen Printing in Selma, Texas] was one of the people who really helped me.”

So, from your first art show to today, much of your growth and popularity as an artist was organic, especially without social media the way it looks and works now. When did you feel like you had amassed a bigger following? What was that first moment you thought people liked your art?

“I had hand-drawn Selena like the Virgin Mary for a Girl In A Coma poster around the mid-2000s. I didn’t think anything of it, but everyone was asking, ‘How much for a poster? Where can we get this poster?’ That’s when I was just establishing myself and thought ‘I need a name.’ Anytime a band, like a famous band, would come [to town], I would ask if they needed an artist or something to promote. We’re now in the internet phase, so we have Instagram and Facebook, so I’m able to contact these people. I’ve been able to network and get in contact with bands I love, so I would offer my services, they would sell my posters at their shows, and people would buy them. It just blew my mind. I was very self-deprecating, so I was [of the mindset], ‘That artwork sucks! Why are they paying so much for this?’”

So many amazing artists in San Antonio do that! I mean, you even have the little box of smaller prints that says “Tattooed Boy Sux” on it.

“I guess my inner hater comes out. I think every artist does it. I don’t think anyone should talk sh*t about any artist because art is subjective, but I go ahead and say what they’re going to say anyway.”

“It was a strange time before social media. Not a lot of people were showing their artwork as much as they are now, so I was scared to show my art, too. It took coaxing from my friends to do an art show.”

But that’s not the reception you get! At Paper Trail, you had a long line curved around Rock Box!

“Yeah, I’m curious about that, because I don’t know. I couldn’t answer why I get those lines. I’m very grateful and thank everyone in line personally. I feel bad for them waiting so long, but I have to thank everyone individually and give them an opportunity for us to communicate. My parents taught me to be respectful, so I give them the time back because they can spend their money on anything, and for them to come to me and for my silly little artwork, it literally still freaks me out and is so cool.”

I would definitely say that adds to your appeal – your sincerity and authenticity is also on display with your art. Your City Prints are particularly popular. What is your process when selecting a new location?

“My artwork is, I guess, relatable, but I’m not taking requests for when I do my City Prints. Those places that I draw – something happened in those places to make it personal. My process is ‘that would be cool on a poster’ while driving through the Westside. There’s a lot of things to draw there that a lot of people from the Westside love that other people from other areas [of San Antonio] don’t know about. I consider them ‘tourist posters for locals.’ Like Brackenridge, my parents took me there as a kid, and just the mention, I knew what to expect – the park, possibly the Zoo and sky rides. I have fond memories, just like many others. It’s therapeutic to think I’m not alone pronouncing ‘Whataburger’ as ‘Waterburgers.’ A lot of people [in this city] can relate to that. San Antonio is just filled with such goodness. There’s going to be growing pains, but I’m trying to keep, in my special way, like the Pig Stand and Lulu’s [Bakery & Cafe] alive. I don’t want those to be forgotten. I try to tell the story through my art.”

I can see why you put Hogwild Records in your North Main print: it’s where you first put your art in a window for everyone to see. I also have a very special connection to that place. I absolutely had to have this print and it was made even better knowing it comes from such a humble local artist memorializing special places in San Antonio. I, myself, am a collector of the City Print posters now. I try to get each one, but they’re limited runs, so I’m missing a couple.

“It’s tough. I don’t even have each of them. The ones that I don’t have, I’m actually trying to get. The Southtown one is in biggest demand.”

And you’re not just rendering architecture—you put your spin on it with all the flying animals and such. How do you incorporate those elements?

“The ‘weird’ stuff I draw comes from weird and interesting dreams. It makes it more eye-catching to put some ridiculous UFO at The Mix. I collected posters from Coop, Brian Ewing. Frank Kozik was one of my major influences in the punk scene. Every time I went to Emo’s [Austin music venue], his artwork was everywhere. That inspired my pop art sensibilities because I used to love Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol. But I’m not Warhol or Lichtenstein or Kozik, so I [asked myself], ‘What can I do to mix up what I know and love about San Antonio?’ I developed my own style.”

Speaking of details, I’ve noticed little Easter eggs, like “Sup!” and “Lala” in your posters. What’s that about?

“My mother Oralia passed away in ’99 and was always supportive of anything creative I did. So, anywhere I can, I put ‘Lala’ [her nickname] because I know she would be proud of what I’m doing today and show all her friends and coworkers. I want to make my family proud, show that I’m making art sustainably and with a clear mind.”

Your sobriety plays a role in your art! One of my favorite pieces is the Todo Chingón print styled like a Topo Chico bottle, inspiring me to “forgive myself.”

“That was my first multi-colored screen print that I sold at Bang Bang Bar, about 20 pieces. I think I got the bar to give anyone who bought one a free Topo Chico. I was looking for something that would make me think I was drinking a beer, but I found a hidden strength. That was like a proclamation, ‘I’m sober, I’m here. I can do it.’ It was a mind-over-matter thing.”

So, I wanted to ask–your art is everywhere at Gold Coffee here in San Antonio. What’s up with that?

“First of all, I support all local coffee shops. Gold has a special place for me. I was struggling with my sobriety and needed some kind of vice. ‘I drink coffee a lot – maybe I could treat coffee shops like a bar.’ I never really go to Starbucks and love to support local coffee shops, but I had never gone to Gold. I tried it out. It was super busy in there. Everyone was friendly. Jason [Tantaros], the owner, recognized me. I was taken aback, like ‘Woah, you know who I am?’ And we just started talking about music and had so many things in common, realizing I was having the same conversations I would at a bar, but I was at a coffee shop! All of us are sober and all hopped up on caffeine. We became super good friends that day. It’s cheesy to say, but Gold’s saved me.”

What about the Edgars?

“It’s not a person; it’s a haircut. I had a rat tail, mohawks, punk hair, and bleach, and that was frowned upon, but I’m not a bad guy! It’s just a hairstyle. They just get this bad rap of hanging around Marbach [Road] and Ingram [Mall] or being criminals, but there’s a lot of good kids. And really, this is like Aztec warrior style. This is coming from the motherland. This is a part of Mexican culture. They’re not stereotypes. They’re just regular kids from the Westside.” [Author’s Note: Jumano Indian men (who were hunters, traders, and emissaries between indigenous people and the colonial Spanish) did, in fact, wear similar hairstyles.]

What place do you think art has in San Antonio?

“The city’s doing more things with the arts. The galleries are amazing. The street art is amazing. I hope San Antonio is known for it. San Antonio artists are rockstars to me. I don’t mean to fanboy, but there’s so many I look up to.”

“But I’m not Warhol or Lichtenstein or Kozik, so I [asked myself], ‘What can I do to mix up what I know and love about San Antonio?’ I developed my own style.”

Speaking of the city and art, how did you land working with our beloved Spurs?

“They already knew about me – I’d always tag [the Spurs on Instagram]. I had done a job, a poster for San Antonio Football Club. I’m not the best businessman, so I did it as a fan, but this paid off. The Spurs’ marketing team reached out and I thought it was a joke, scam email. I emailed them back and they set up a meeting. They wanted me to do what I do and gave me creative freedom. They didn’t want to tell me what to draw, but were hoping to draw a San Antonio neighborhood, a place in San Antonio with puro sensibility. So, I drew a little neighborhood, Culebra Park, two minutes from the house I grew up in. It was an honor to do that. I’m still in disbelief – family members wearing shirts and tagging me.”

What does puro mean to you?

“Puro is for San Antonio only. It means family to me. I’ve traveled and it seems like people say ‘hi’ and nothing else. I can have a conversation with a stranger for days here and talk about, ‘Remember that bridge, business, grocery

store that was here?’ You can go up to anybody in San Antonio and have a conversation about anything. It’s the sense of family, culture, and community all rolled into one. And when I’m out of the city, I rep it. Hard. People wear their Spurs jerseys at the Eiffel Tower—they want people to know where they’re from.” ■

This interview has been edited for conciseness and clarity.